Bernard Joseph Francis Lonergan SJ, CC, liked to laugh. He liked Goldie Hawn in the movies. He liked Jane Jacobs too. Not because she was funny but because she was smart. He called her Mrs. Insight. Not as smart as he was, of course. In that he stood alone.

Pammy’s great2granddaughter Eileen had dinner with Lonergan the evening of February 19, 1981. That afternoon he asked to borrow a copy of Eichner’s Guide to Post-Keynesian Economics from the library at Montreal’s Thomas More Institute. He explained that it would be good to have at hand for his visit with Eileen. They knew each other well. Eileen had written her doctoral thesis on Lonergan’s economics. But she was somewhat shy and he was somewhat introverted, neither of them big on table talk. Economic theory would be easier for both.

He was in town from Boston College, where he held appointment as Distinguished Professor. He had consented to a week of interviews by disciples who wanted to mine the fatherlode before it petered out. He was 76 years old, a survivor of cancer surgery with one lung carved away from three decades of pipe smoking, who would be in declining health during the few years left before he died in November 1984.

The outcome of the talks at TMI would be a slim volume of Q&As, Caring About Meaning, privately printed by the Institute and dealing with “patterns in the life of Bernard Lonergan.” This transcript “moves around,” writes the editor, “as in any good conversation. There are frequent and abrupt changes of topic, some repetitions, and the casual use by Father Lonergan of Latin, Greek, German and French,” some of the languages in which he was proficient.

In marked contrast to the simplicity of this memoir are the academic surroundings in which the boy from Buckingham is enshrined today. There are gatherings worldwide to discuss his meaning. The Lonergan Research Institute in Toronto and the Marquette Lonergan Project in Milwaukee are jointly digitizing and preserving his papers, sponsoring seminars and publishing newsletters to describe the thriving world of Lonergan studies. There are Lonergan Centres at seven universities and at least another seven independent Lonergan Institutes in places as diverse as Nairobi, Mexico City, Montreal, Sydney and Innsbruck. The University of Toronto Press is publishing a compendium of his works in 22 large volumes at a cost north of $1 million. They’re on the market for prices as little as $18 for a paperback, or up to $114 for clothbound major works. More than 500 hours of his lectures, delivered and taped between 1957 and 1980, are being remastered to CDs. Three decades after his death he has become an academic industry with branches on all continents.

Major international collocutions are scheduled on topics such as “Lonergan’s Insight After Fifty Years: Its Origins, Its Meaning, Its Reception and Prospects,” on the agenda for one of the annual symposia at Marymount U. in Los Angeles. In 2013, for the 40th annual workshop on his work at Boston College, the Lonergan lens is on the “50th anniversary of Vatican II.” Workshops are also scheduled this year for Jerusalem and Melbourne, Australia.

He was the great grandson of a saloonkeeper. Hugh Gorman was among the early settlers of the lumber town of Buckingham, on the Quebec side of the Ottawa River. It was largely an Irish community to begin with but later became and remains primarily French speaking. Lonergan’s father was an engineer and surveyor who was away much of the time, marking ways for rail lines through the Canadian northwest. His mother, remembered even today as particularly pious, prayed the rosary three times daily and was the foundation of the home, assisted by her spinster sister Mollie.

A precocious student, he was reading Treasure Island at six and went through four years of high school in two. Much of his drive for learning he attributed to formation at the Buckingham primary school, where the Christian Brothers organized students into three sets of three grades. “I had the advantage — in the ungraded school you kept working. If you had one teacher talking all day long, you just wasted your time.”

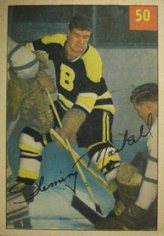

Young Bernie enjoyed all the usual pursuits of small town Canada. His delight in winter sports was amplified by the exploits of his cousin, Ed Gorman, who would go on to play in the mid-1920s for the original Ottawa Senators. One of the founding clubs of the NHL, contender for 11 Stanley Cups in 17 years of which it won five, this team was voted the greatest of the first half century by Canadian sports editors in 1950. Another player among the Silver Seven, as this great team was known by fans and sportswriters, was winger Jack Mackell, who married Pammy’s great-granddaughter Margaret (Kate’s niece) in 1922. Their son Fleming Mackell, Pammy’s great2grandson, also won a couple of Stanley Cup rings. Ironically, he got both during his three season run with the Toronto Maple Leafs, while he made his reputation in the game as a rugged all-star centre and alternate captain with the Boston Bruins.

In summer Bernie Lonergan went river rafting on the Lièvre River, which drained a vast region of virgin forest and flowed to the Ottawa River four miles south. He wasn’t altogether free of mischief. He taught his two younger brothers to play poker and took their money at cards, returning it only after they threatened to tell their parents. One of these siblings, Gregory, also joined the Society of Jesus and was able to stay with Bernie at the Jesuit infirmary in Pickering to provide palliative attention during the distressing last year of his life (1984), when he was afflicted by depression and a long-simmering addiction to alcohol as well as the ongoing effects of the cancer surgery.

He waved goodbye to Buckingham at fourteen to study at Loyola College in Montreal, now a division of Concordia University, but then a Jesuit-run liberal arts college which was organized, he would write some years later “pretty much along the same lines as Jesuit schools had been since the beginning of the Renaissance, with a few slight modifications.” After schooling, he would return home only occasionally as his work took him further and further afield (late in life he would count that he had been “across the Atlantic about forty six times”). But Buckingham remembers him. The town’s public library is the Bibliothèque Municipale Bernard Lonergan and a plaque at the door reads, “Born in Buckingham, member of the Order of Canada and considered by many intellectuals as the best philosophical thinker of the twentieth century, he was a Canadian Jesuit philosopher and theologian of world renown.”

A philosopher and theologian indeed, also an economist of original perception, though most who look carefully at the vast expanse of his work conclude that none of these labels really capture him. He was essentially a methodologist, whose vocation was to teach how we can “appropriate our own rational self-consciousness,” by which he meant understanding the operations of experiencing, understanding, judging and deciding as we perform them in our daily routines. But first and foremost he was a Jesuit, which provided both his greatest support and his greatest frustration.

At Loyola “I acquired great respect for intelligence,” he would say years later. “The Jesuits were the best educated people I had ever met.”

As much as anybody, once Jacques Cartier had found the place for Europeans, the Jesuits made Canada. The Society of Jesus was founded in the mid-16th century by Ignatius Loyola and immediately set to work to counter the reformation being promulgated by Martin Luther. Their primary tool would be education — Ignatius Loyola, founding “general” of the Society and his first half-dozen recruits were all doctoral students at the University of Paris — that they deployed in order to strengthen faith, gain converts and cultivate influence, both within the Church and beyond. Education was the hottest product in the cultural arena as literacy began its run following Gutenberg’s marvelous invention barely a century before. As the Society’s origin coincided with a great age of exploration, discovery and settlement in new worlds — the age of Cartier, Columbus, Cabot, Verrazano, Hudson and hundreds more — its schools spread worldwide, some to become major universities (Université Laval in Quebec City, among the oldest institutions of higher learning in North America, would evolve out of the Collège des Jésuites). Many members of the order through the centuries became renowned scholars and scientists, making significant contributions particularly in fields such as astronomy and anthropology. And they became inveterate travelers, carpetbaggers of the church, seeking to spread the Roman Catholic faith throughout North and South America, and in the far east, particularly China (even today the largest Chinese dictionary in a western language is a Jesuit publication of 9,000 pages).

The first Jesuits to reach the land that would become Canada were Pierre Biard and Ennémond Massé on May 22, 1611. They and many who came after them went to live among the native nations. They followed the wanderers through forests, along waterways and across long portages. They acquired some fluency in aboriginal languages and customs, and served as interpreters, guides and go-betweens for the early traders and colonizers, who could hardly have survived the harsh climate, rocky soil and distant treks to fur-bearing resources without this assistance. Some blackrobes set out to explore the vastness of the American continent. Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit priest, and Louis Jolliet, who studied eleven years with the Jesuits but backed away from ordination at the last minute, were the first Europeans to reach the Mississippi. Others taught, baptized and ministered to the settlers and “sought to insulate the Natives from the consuming ravages of greed.” The annually published Jesuit Relations, begun as reports from missionaries in the field to superiors back home, gradually evolved into travelogues and adventure tales circulated in Europe to attract immigrants and enlist support for the mission. As colonial powers began to negotiate treaties with aboriginal inhabitants during the 18th and 19th centuries, Jesuits acted as counselors and interpreters in an effort to protect indigenous interests. That they were not always, or even often, successful was acknowledged by Peter-Hans Kolvenback, the General of the order, in 1993. He offered the Society’s apology to American Indians for “the mistakes it has made in the past (when) the church was insensitive toward your tribal customs, language and spirituality.”

The million or so Canoriginals today are proportionally much more numerous than their cousins in the United States. There, indigenous peoples were not regarded as trading partners but as barriers to western expansion. They were cut down like trees in the forest so that white Americans could achieve their manifest destiny, range their cattle and farm their fields. Jesuits were among those who imprinted a pattern in Canada that moderated the military violence and wanton massacres so common south of the border. (Which is not to say that Canada treats its indigenous peoples fairly and justly. It doesn’t.)

Jesuits were intrepid to the point of sacrificing their lives. Jean de Brébeuf and seven companions are canonized as saints of the Catholic Church. In their memory each year on Sept. 26 a reading of the religious ‘office’ proclaims that their lives were “like a martyrdom because of the character and wretched conditions of the Huron Indians of that time.” In the mid 17th century the Hurons were wiped out by the Iroquois and blackrobes were among the casualties of conflict, some of whom “endured almost unbelievable tortures with such invincible courage as to arouse the admiration of the savage executioners themselves.”

The Canadian Encyclopedia says “the torture and death of blackrobes Gabriel Lalemant (left) and Jean de Brébeuf (right) in 1649 was one of the most powerful images distributed of the New World, not least for its value as propaganda.”

It should not be hard to imagine why impressionable young men are attracted to this adventurous, historic band of brothers. I dare say that almost everybody who spent as much time at Loyola as Lonergan did, or I did, gave some thought at some time to joining the Jesuits. They are figures of authority and of mystery, a fraternity with great traditions, who opened many frontiers for European civilization in new found worlds and ancient. They had been advisers to emperors and teachers of princes. They also had been persecuted, martyred and, for forty years in the 19th century, disbanded under a papal prohibition. There were some places in the world where the ban was not rigidly enforced and one of them was Quebec. By going underground and keeping the dream alive the Jesuits survived and eventually were allowed to raise their head again. They were a magnetic draw for boys (there were no girls at Loyola then, nor in the Society of Jesus).

I gave it a few days consideration before concluding that the strict vows of poverty, chastity and obedience required of Jesuits were not for me. The fathers bent little effort to persuade me otherwise. Some of the more courageous among my friends took the spiritual path, among them David Asselin, who would have become a brother-in-law had he not died so young; and Jean-Marc Laporte, a philosophy wunderkind who dazzled us in caf and coffee shop sessions with his grasp of subtleties in Aquinas, Scotus, Kant and other lights, including the recently published Bernard Lonergan. After long apprenticeship (the road to full membership in the Society of Jesus stretches fourteen years) Laporte would become Lonergan’s personal secretary and in 2002 he was appointed Provincial, the highest administrative post of the order in English Canada (Jesuits long ago divided Canada into just two provinces, English and French). Provincials report to the Jesuit General in Rome, who reports to the Pope. In fact the General is referred to by scoffers as the black pope. Jesuits are the papal legion, canonically speaking. (This was written before the election of Pope Francis, an unexpected event that likely portends more change for the Church than for the Society, which seems to be dong better than its founder Ignatius could have dreamed.)

Former Chapel (now F.C. Smith Auditorium) on Loyola Campus. Mary Blickstead and I were married here in December 1958.

When I was at Loyola, through most of the 1950s, the Thomas More Institute was a centre of continuing education and intellectual discourse for adults, and so it remains. Founded by Eric O’Connor, a Jesuit and Harvard-educated mathematician, it was here in 1945 that Lonergan began to think through a centrepiece in the ever-expanding universe of his thought. Though Insight: A Study of Human Understanding , would not be published for another dozen years, it was in a series of lectures at TMI that the brilliant, middle-aged professor found inspiration to begin writing what would quickly be recognized as one of the most original and profound philosophical works of the 20th century. Of its origins at TMI he would later say, “It seemed clear that I had a marketable product not only because of the notable perseverance of the class but also from the interest that lit up their faces.”

The spark had been struck but it was soon in danger of being extinguished as year after year, for more than a decade, he was consigned by the order to teach in institutions that he found intellectually stagnant. His personal standard for education was set somewhat higher than the Society’s. When he was sent to Europe as part of his Jesuit training he found he had to work harder just to catch up. “I read Thackeray and made a list of all the words,” he said, “to know the meaning well enough to use them myself. I looked them up in the dictionary and wrote them down and went over these lists; if I still didn’t know the meaning I would look up the dictionary again. I improved my vocabulary tremendously. But I went to England for philosophy, and all the lads there were talking that well!”

Years later he would write to a superior, “At the parish school I always had to work my hardest. At Loyola my acquired habits did not survive my first year: by the mid-term exams I was in 3rd High; by the end of the year I was fully aware that the Jesuits did not know how to make one work, that working was unnecessary to pass exams, and that working was regarded by all my fellows as quite anti-social. For my remaining three years at Loyola I loafed and passed exams with honours . . . Now do not tell me that I am exceptional. I have more than average ability, but not so much more that I did not have to work when confronted with the standards of the parish school in Buckingham or the University of London.”

Only the strict vow of obedience he had taken kept him on course. In the Society of Jesus, he would say in later years, “you have to do things that are rather hard and you need a lot of grace to do them. That is the advantage of a religious life.”

In the early 1950s the advantages were not evident. The grind of teaching scholastics (Jesuit apprentices) year after year in Montreal and Toronto was wearing him down. Then his superiors relented. In 1953 he was dispatched to begin a dozen years as professor of theology at the world-renowned Gregorian University in Rome. Apparently he had passed the test of obedience.

He finished the last seven chapters of Insight in a white heat between December 1952 and August 1953, fired by the titanic orchestrations of Ludwig van Beethoven. Insight sold out its first printing within a year, “a best seller of its type,” he once quipped. It has since been translated into all European and several Asian languages and still sells thousands of copies annually. I fear to put it this simply, but since he repeats it a couple of times in Insight, I’ll say its premise is that by understanding what it is to understand “not only will you understand the broad lines of all there is to be understood but also you will possess a fixed base, an invariant pattern, opening upon all further developments of understanding.”

Putting Insight behind him, Lonergan turned to shedding new light on old theological questions. At the Gregorian as many as 650 students would crowd into his classes, and the works he produced there had an unusual feature for a modern author. They were written in Latin. He was also fluent in Italian, German and classical Greek, all important to pursue his theological and philosophical studies, and French. Perhaps not surprisingly for a Quebec-born Canadian of his era, he didn’t learn French at home. In Buckingham “we didn’t speak French. That depended on what part of the town you were from. And the hardest place to learn French is Montreal. I learned French in England.”

In fact Insight had never been the end that Lonergan had in mind. His overriding concern was to bring to the 20th century the kind of synthesis of modern thought with theology that Thomas Aquinas had achieved in the 13th century and that had endured, sometimes in observance sometimes in ignorance, for some 800 years. He agreed with Aquinas that philosophy did not consist in knowing what others have said, but in seeking and finding what is true. Bringing to bear the findings of physics and mathematics, often in dialogue and exchange with Eric O’Connor, he built on Aquinas with practical examples just as Aquinas had built on Aristotle’s first principles.

He didn’t delude himself that altering the classical perspective would be easily accomplished. “Centuries are required to change mentalities,” he would say, “centuries. You don’t get a change of mentality by introducing a few fads.”.He found it necessary first to consider the fundamental question, “What is it to know?” The answer he put forward in Insight would have effects far beyond philosophy and theology. His long-time Jesuit friend and biographer, Fred Crowe, points out, “his political thought has been found relevant to problems in the Philippines; his social thought was the focus of a study group in Mexico; his notion of values was used in an analysis of rural development in Ethiopia; doctors and nurses are applying his ideas in their field of health care; there have been similar applications to Anglican moral theology, to Quaker spirituality, and to Australian and Chinese contextualization of theology; to theories of architecture, chemistry, feminism, to jurisprudence and to psychotherapy . . .” In Ottawa his method is used to train border guards how to tell who’s slippery in the line. There is no end in sight.

His shift forward into theology was given a hard check in 1965 when lung cancer was diagnosed while he was on a return visit to Toronto. He remained for radical surgery, first to remove the lung and then to reshape the ribcage. Recovery was slow. He never returned to his Rome professorship. Instead he began to formulate what would become his second masterwork, Method In Theology, which would be published in 1972.

Theology, he points out “is a reflection on religion, it isn’t being religious.” In Lonergan’s view “contemporary theology and especially contemporary Catholic theology are in a feverish ferment. An old theology is being recognized as obsolete.” Not just theology, but all handed-down classical ‘truths.’

“What breathed life and form into the civilization of Greece and Rome, what was born again in a European Renaissance, what provided the chrysalis whence issued modern languages and literature, modern mathematics and science, modern philosophy and history, held its own right into the twentieth century . . .

“Classicist philosophy was the one perennial philosophy. Classicist art was the set of immortal classics. Classicist laws and structures were the deposit of wisdom and prudence of mankind. This classicist outlook was a great protector of good manners and a great support of good morals. But it had one enormous drawback. It included a built-in incapacity to grasp the need to change and to effect the necessary adaptations.”

Lonergan does not attempt a new or revised theology per se. Rather he creates a process, a method of drawing on the past to enlighten the future. It is not confined to theology but can be applied, as Fred Crowe puts it, “in philosophy or theology, in the pursuit of any project in the field of human studies and human sciences, be it theoretical or practical, present or future, peculiar to one culture or another.”

Though his strength had been sapped by the surgeries, he believed that his desire to finish this project “was a psychological factor in my recovery.” Writing didn’t come fluidly to him. “I write and rewrite and rewrite and rewrite and rewrite and rewrite, eh . . . I could have written more by taking another ten years. But you get sick and tired of a subject and you call it off. Books aren’t finished; authors get tired.”

For relaxation Lonergan often saw films in the company of younger Jesuits who wouldn’t pester him to expound philosophy, and developed an appreciation for the talents of Goldie Hawn. He enjoyed a good joke and could tell one. He read widely, chuckling through Waugh, Chesterton and Lewis Carroll. He championed the work of urban guru Jane Jacobs, whom he dubbed “Mrs. Insight.” Insight occurs with respect to concrete images, not abstractions, and Jacobs is very much grounded in what’s real. But he was no casual conversationalist. In general he displayed a modesty approaching shyness. And while he had a photographic memory and amazing powers of retention for what he read, he was not swift at repartee. The telling comment or response to a question often would occur to him hours after a conversation had ended. He described himself as a “forty eight hour man, strong on l’esprit d’escalier, the witticism you think of when you’re going down the stairs.”

Lonergan’s interest in economics was stimulated by social disruption in the first instance and, in the second, by the quandaries that the profession was experiencing. These instances were separated by some forty years. “When I came back to Canada in 1930,” he said, “the rich were poor and the poor were out of work. The rich were trying to get money selling apples on the street. Many theories were floating around.”

Pammy’s great2granddaughter Eileen

Eileen, his dinner companion while visiting Montreal to be interviewed for Caring About Meaning, wrote in her review of the economics volumes in the collected works, “Both the 1930s and 1970s were periods of ferment in economic theory because of the major structural changes and crises that were not explained satisfactorily.”

His response was to identify two separate but interactive levels in the economy that produce wealth and income in different ways. The surplus sector produces goods for further production, e.g. rails for railroads. The basic sector produces goods for consumption. As well, when prices rise, workers demand more and the wage-price spiral begins. When prices fall, producers pull back from investing and recession begins. The result is often panic and “panic doesn’t get you anywhere; it is just stupidity, loss of nerve.” He proposes an economic policy based fundamentally on a strategy of education, generating widespread understanding of the way these cycles work and the natural interconnection between them.

He was far from embracing socialism, “which doesn’t work very well.” He believed that “the trouble with the welfare state is that it crowds out investment, and if you crowd out investment the economy goes to pot.” But he favoured creation of benevolent enterprise, small-scale industries that employ people who can’t be taught much, or who can’t find jobs elsewhere. Also, “If you can have government deficits to conduct wars, you can have government deficits for a war on poverty, a war on ignorance, a war on ill health, and so on.”

The first International Lonergan Congress was held in Tampa, Florida in 1970, attracting eminent theologians and other thinkers from around the world. One of the participants was former senator and presidential hopeful Eugene McCarthy, a devoted Catholic who once had given thought to becoming a Benedictine monk. When an eminent intellectual remarked, “there are large gobs of Insight” he didn’t understand, McCarthy quipped, “You’re the first to admit it at breakfast. Most of us wait until afternoon.”

The following year Lonergan was invested as a Companion of the Order of Canada, the highest rank.

Lonergan’s invitation to self-appropriation is also an invitation to self-development through self-criticism and self-evaluation. Professor Ken Melchin at Ottawa’s St. Paul University writes in his introduction to ethics, Living With Other People, “More than any other author, Lonergan makes self-discovery the central activity of philosophy and theology. While much of his writing is theoretically complex, it is everywhere guided by a single purpose, the understanding of ourselves in our everyday acts of understanding.”

It sounds straightforward yet, as Fred Crowe says, “the full extent of his influence will not be seen for many years yet. His chief contribution was the creation of an instrument of mind and heart for others to use, whose worth will be discovered not only in study but also in implementation. Only the slow process of history can measure the enduring stature of this great thinker who belongs to the world as much as to his native Canada.”

In a lecture just after Insight was published, Lonergan said: “Your interest may be to find out what Lonergan thinks and what Lonergan says, but I am not offering you that, or what anyone else thinks or says, as a basis. If a person is to be a philosopher, his thinking as a whole cannot depend upon someone or something else. There has to be a basis within himself; he must have resources of his own to which he can appeal as a last resort.”

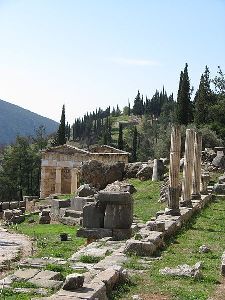

Know Thyself. It was inscribed on Apollo’s Temple at Delphi in southern Greece and has been a precept for human action since before the time of Socrates. But it has famously defied easy doing. Lonergan doesn’t promise to make it any easier. But he may well be the first and only oracle to nail precisely how it can be done.

A most enjoyable and thought provoking insight into one of the modern world’s great thinkers. Thanks, Scansite!

Thank you for this interesting piece, it has motivated me to do more reading about, and by, this important philosopher … Nicely done, and thanks for sharing!

I take it you don’t remember him from your time at Loyola?

K

Date: Wed, 6 Mar 2013 22:33:16 +0000 To: kerrincooks@hotmail.com

I knew him but not well and remember him. He was often talked about by Fr. McGuigan, whom I considered a mentor at that time and who was close to Lonergan. I think he did some work on the Insight manuscript. I attended a seminar he gave at TMI (in fact I presented a paper at it, as I recall) and a social evening with him at Nicky Laflamme’s parents’ home (later found that Nicky and Bridget were distant cousins). A woman I won’t identify who was there gushed to Lonergan that she had “stayed up all night to read Insight” when she heard he would be there.

Hi, Tony, A really interesting article; I’m glad you sent the link. It reminded me of that seminar I attended at St Mary’s in Halifax that Lonergan gave on Insight. Most of it was over my head, I think. It was, though, a revelation to see a giant intellect at work. During the question period following each lecture, when he was asked a question relating to another author, he’d contextualize his answer, often by quoting from memory the respective author in his own tongue, so we’d hear Kant in German, Aquinas in Latin, Descartes in French, etc. We had one afternoon off, as he was giving a lecture on psychiatry to psychiatrists. On another afternoon, I saw him come into the library, quickly browse some shelves, pluck a volume titled Oriental Despotism and sign it out. Just another indication of his breadth. I’m happy he liked Jane Jacobs. By coincidence, I’m currently going through The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

Best, Tony

“What breathed life and form into the civilization of Greece and Rome, what was born again in a European Renaissance, what provided the chrysalis whence issued modern languages and literature, modern mathematics and science, modern philosophy and history, held its own right into the twentieth century . . .

“Classicist philosophy was the one perennial philosophy. Classicist art was the set of immortal classics. Classicist laws and structures were the deposit of wisdom and prudence of mankind. This classicist outlook was a great protector of good manners and a great support of good morals. But it had one enormous drawback. It included a built-in incapacity to grasp the need to change and to effect the necessary adaptations.”

Essential Euorocentric thinking… led to the genocide of Native peoples here… ongoing… yay Jesuits?

You fail to indicate that the passage you insert is a direct Lonergan quote from the article above.

Your dismissive concluding sentence ignores this passage that follows in the text:

“The million or so Canoriginals today are proportionally much more numerous than their cousins in the United States. There, indigenous peoples were not regarded as trading partners but as barriers to western expansion. They were cut down like trees in the forest so that white Americans could achieve their manifest destiny, range their cattle and farm their fields. Jesuits were among those who imprinted a pattern in Canada that moderated the military violence and wanton massacres so common south of the border. (Which is not to say that Canada treats its indigenous peoples fairly and justly. It doesn’t.)”

I’ve just been reading a bio-cum-commentary of Lonergan and once again I’m amazed at how close he was to Hank Smeaton, some would say his only friend, not to mention the high esteem Lonergan held him in and expressed in correspondence with superiors. There must have been more to Smeaton than we ever caught wind of.

Re Smeaton, yes, it seems strange to me that he would be liked and respected without serious reservations by anyone who really knew him. He was one of the weirdest of the Jebbies I ever dealt with, both as a teacher and supervisor during my boarding years, and as a farcical basketball coach. He was clearly very intelligent and learned, but in a freaky, semi-autistic sort of way, prone to digress into extended recitations of arcane factoids. When the Eskimos won the Grey Cup in my freshman year, he walked into class and wrote on the blackboard: “AMATOS HOS BARBAROS SEPTENTRIONALES!”

BTW, I’ve read your stuff about Lonergan, and I still find something missing: a nice little summary of the essential contribution he made to philosophy. You say a lot about his relevance to a lot of different fields, but almost nothing about what that relevance was or is. You can sum up Kant about the categorical imperative, and Plato about the world of ideals, and Aristotle about act and potency, etc., etc. What’s the equivalent kernel of Lonergan?

That’s quite a BTW. You’d like me to sum up Lonergan’s philosophy, embedded in the 25+ volumes of the UofT collected works and the daily workload of professors in Boston and Toronto, as well as partial commitment from participants in Lonergan Institutes around the world issuing god-knows-how many pages per hour of analysis and belief. Well here goes.

He took the long view, a thousand years, ten thousand. His message was about the perfectibility of man through self-appropriation, leading to a more civilized existence for all. Like Placide, I think he’s willing to be flexible about what god means.

I wasn’t really expecting you to do the summation; I assume that various deep-dish students of his works have already done this. That’s how kernels of the thought of other philosophical biggies have been distilled over the years. You don’t have to read Marx to learn the essentials of communism, or worse yet, read the incomprehensible Hegel to learn about thesis, antithesis and synthesis. Big-name philosophers tend to be associated with one or two big ideas, like Nietsche’s superman and dead god. The sheer volume of Lonergan material you cite raises questions of quality versus quantity. After all, there are probably 100 pages or even 1000 about Jesus out there for every one there is about Lonergan, but this is not a reliable indication of worthwhile content in ideas, thoughts or analyses. Can you expand a bit on “perfectibility through self-appropriation”? I have no idea what this means.

I still feel that it’s all contained, or at least adumbrated, in the “understand what it is to understand” sentence that he thrice repeats in Insight, you recall . . . “and not only will you understand the broad lines of all there is to be understood but also you will possess a fixed base, an invariant pattern, opening upon all further developments of understanding.”

But the more I explore, the more it seems to me that he’s not so much interested in the concepts as in use of the method to improve the state of mankind. His theological approach, I gather from commentary since I haven’t delved into this third of his pursuits (philosophy and economics the others), is to urge not the development of theology but the development of theologians, particularly by introducing them to the sciences.

This is good, and I should have remembered reading this myself. However, it still sounds more like an aspiration than an achievement. Discovering an invariant pattern or process that underlies or enables understanding would certainly have important consequences, but what and where are they? Did Lonergan actually “understand what it is to understand,” or did he just try to do that? I didn’t come away from Insight with any such understanding. Did you?

You only get it when you understand you’re not supposed to get it, at

least not readily. It’s an exercise. He’s tossed a few kernels into an

elevator of wheat. The question is why?

I start with what I think his real purpose is. He writes, “the people who

are seeking to influence history . . . have to be people in whom the horizon

is coincident with the field.” He uses horizon as the distance we see and

the field as the end distance. He’s looking to find (produce? Ever the

Jesuit) exceptional people who can see as far as there is. And he’s taking a long view, since he perceives humanity currently treading at the tadpole

stage. When asked when he thought he’d be heard he said a hundred years.

It’s already more than fifty.

Still, serious human thinking is difficult work. How can people be induced

to undertake it? The way he found was to produce a compelling and dramatic promise – understand what it is to understand and the world will unfold before you – that draws people in. In no time most are lost in the field just following the few who actually do get it, which is that there’s nothing really to get other than to exercise our powers rigorously. The objective is enlightenment through five transcendental precepts: Be attentive. Be intelligent. Be reasonable. Be responsible. Be adventurous. The collected works are a western form of koan. Bernie is Buddha.

Needless to say, my take is not orthodox and likely would be ridiculed by

the berniecrats.

By some strange osmotic I realized after writing this that the bio I had

been reading earlier, “Bernard Lonergan: His Life and Leading Ideas,” has

two quotations as Frontispieces. Both are teachings of Buddha.

Thank you for this. It is genuinely enlightening. It took me back to the years I spent in the 70s investigating Buddhism and especially Zen. If I’m getting this, Lonergan is saying that, while we’re probably unable to really understand what understanding is at this point, the effort to do so is in itself enlightening, and may even lead to an answer sometime in the distant future. This comes very close to the conclusion I derived from Zen: the ultimate answers are unobtainable, but searching for them anyway is the road to enlightenment. The ultimate answer to your deepest questions is the realization that your questions have disappeared, or never existed in the first place. Thinking about this led me back to some old notes, including this little poem:

When you understand, you belong to the family;

When you do not understand, you are a stranger.

Those who do not understand belong to the family,

And when they understand, they are strangers.